My Story - Asian Americans Fighting in Vietnam

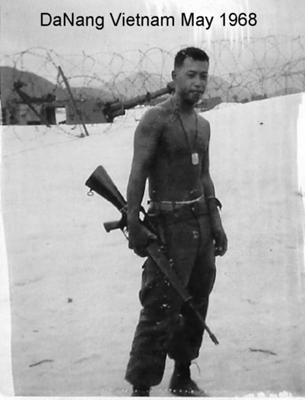

by Sel Louis, USMC

(San Francisco Bay Area)

I am Chinese and wanted to be like everyone else in the Caucasian community we lived in. Marin County in Northern California was an ideal place for an Asian American to blend in. It almost seemed they were color blind and the free spirit of the 1960's made it all the easier to fit right in.

I was served with a draft notice in the summer of 1967 and made my decision to enlist in the Marines versus being drafted in the Army. In retrospect, it was a decision made from watching too many war movies and the need to further differentiate myself as someone who really wanted to be as all-American as anyone else in our community.

After a warm sendoff, reality hit during my very first hours of Boot Camp in San Diego. I quickly realized that we were at war with people that looked just like me. It also did not help that the legacy of the Marines were built around the Pacific War of World War Two and the Korean War where the enemy were Asians.

After a somewhat sheltered life where discrimination was not overtly evidenced, I now found myself at the center of attraction for being Asian or a "gook."

Marine Boot Camp in itself is one of the most physically and mentally challenging experiences any sane person would ever care to endure. During a time when America was at war made the training that much tougher as most of us would be expected to be shipped overseas at the conclusion of training.

Being Asian singled me out as a repeated reminder of what the enemy will look like. I was always volunteered by my peers to be the example in any hand-to-hand demonstration or to don black pajamas like a Viet Cong during mock battles.

Outside of Californians, recruits from other parts of the country rarely associated with Asians and for some from the deep south, I was their first encounter with someone of my race.

These were hard times and I often wondered if I would survive the 13 weeks of Marine boot training. My resolve was that I was going to see this through.

I was blessed with above average athletic skills and I also had completed one year of college which placed me at a higher intellectual level than many of my peers who just barely managed to complete high school. At that time in my life, I was more prepared to meet the challenge than at any other time in the years to come.

Marine Boot Camp did teach us to operate as a team and as a team, there could be no weak link for it would mean eminent failure. As the weeks passed, less attention was placed on me as a rarity and our platoon developed a true sense of unity.

We succeeded as a unit and we learned to watch each other's backs. These were the attributes that would have dire consequences in the near future as we prepared for action overseas. True to form, I was able to assimilate into Marine Corps life over the weeks and made friends with other platoon recruits as graduation drew near.

I later learned that there were several bets within the ranks of the Drill Instructors that the "gook" in Platoon 3074 would never make it past the third week of training. Again, I was able to be more "American" than most and cleared another hurdle.

But I learned first hand that I was different and there would be greater challenges in the coming months.

Christmas 1967 was very special. I had just concluded advanced infantry training and scheduled for combat training in field artillery at the beginning of the next year.

I had also received orders for the WestPac theatre, which meant I would be sent overseas. All of us knew that WestPac orders meant duty in The Republic of South Vietnam. Timing was everything, and I was home for the holidays on a two-week leave during Christmas.

Though the atmosphere had changed since my departure to boot camp in the early Fall, people were still patriotic and welcomed me home with opened arms. But one could feel there was a change on how the war was being perceived. Nonetheless, I was home and still had that feeling of invincibility that all young people seem to posses.

All too soon, my leave was over and I was headed back to whatever the Marine Corp had in store for me. I never realized that this would be the last time I would see the world as I remembered it prior to 1968.

I was able to make it home one last time in February of 1968 just days before I was to be sent overseas. It was a weekend leave that I was able to take advantage of because going home only meant an hour plane flight from Southern California to the San Francisco Bay Area.

The political climate had changed substantially since I was last home. President Johnson was escalating the war and the nightly news continually brought the war home. The TET Offensive had just occurred in January and Americans finally realized we were in a real dogfight.

A heavy

I left for the airport that Sunday afternoon after saying goodbye to my parents. They were simple folks that had tried to make their way in the United States like everyone else and were now sending a second-generation son off to an uncertain future.

Some of the invincibility from my last visit home wore off. I finally started to realize the important role we all had in the coming months, and the responsibility was overwhelming during that flight back to Camp Pendleton.

Contrary to what I thought would happen, our staging battalion arrived in Da Nang in February of 1968 and quickly dispersed into other units in accordance to Military Occupation Specialty (MOS). By the time I was finally processed, there were only two us left that were scheduled for transfer into an Artillery unit about 15 miles Northeast of Da Nang.

Rather than arriving as a complete unit, we arrived as replacements. This meant earning the trust all over again of fellow Marines. In my case, being Asian brought on a whole new meaning for being truly different.

Most of these guys had been in country for several months and had a rooted disdain for anyone Asian. Can't really blame them for the horrors they must have endured fighting against people that look exactly like me.

Again, I had my challenges except this time, the stakes were much higher.

The first few weeks were a blur that extended into months. All of a sudden, I was no longer a new guy and an oddity. Just as before, my uncanny way of assimilating into situations made me just another Marine.

1968 was a pivotal year for the armed forces in Vietnam. The war was escalating, the country was divided back home on whether we should be there at all, and the casualty rate was mounting at an alarming rate.

That innocent and romantic glow of going off to war had become a distant memory. There was no more sense of invincibility, and as a young man of 20 I had already witnessed things that most people would never see in three lifetimes.

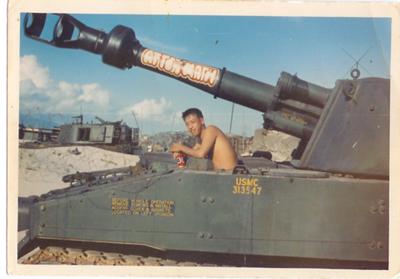

By the sixth month in country, I became one of the better artillery gunners on the gun line. We had become a killing machine, but it was not up close and personal. We were hitting targets that were miles away with forward observers confirming kills once the fire mission was over. This would happen on a daily basis with most days having several fire missions.

I always prided myself at being good at whatever I ventured into. It is now after many years later that I wonder how many young men would never go home again because I was good at my task.

One day we had a chance to go into the Air Force Base in Da Nang for a meal after being out in the field for two weeks. The Air Force had a base mess hall better than any we had in the United States. They had a comfortable and sheltered life, even in a war zone.

We were unshaven, dirty, and exhausted and all we wanted was a meal and some rest before going back out again. I was in a truck with several other Marines when an Air Force MP stopped us at the gate. He had on pressed utilities, a spanking clean white MP helmet and you could not help but notice the high gloss of his boots. He asked us to check our weapons at the gate because they were not allowed on base.

He also looked at me and said I would not be permitted on base because non-documented Vietnamese could not enter for security purposes. I was just about to protest when one of my fellow Marines grabbed the MP by his shirt and said I was a United States Marine and if he insulted any Marine again, he was going to shoot him on the spot.

It is now after many years that I can look back at this and surmise there is a lesson to be learned. But in a time when we had other matters to worry about, it was just a routine incident that was quickly forgotten.

Christmas 1968 came and it also marked a time when I would have less than three months to go before returning stateside. I will always remember this Christmas as it was the first time many of us were away from home.

Spending the holiday season in hostile conditions brought on new meaning to being homesick. But then again, surrounded by people you could truly trust your life to is an experience that many non-combatants will never experience.

There is an unspoken sense of brotherhood that only a very small percentage of us will ever come to know. These fellow Americans only averaged 20 years of age yet had the wisdom that only comes with facing life's uncertainties on a continual basis.

Story to be completed at a later date . . .

Sel, thank you for sharing your story. We look forward to receiving the rest of it.

Comments for My Story - Asian Americans Fighting in Vietnam

|

||

|

||

If you didn't find what you're looking for, use the search bar below to search the site: